The Hidden Blueprint: Decoding the Axolotl's Limb Regeneration Secrets

In the murky canals of Xochimilco, Mexico, an unassuming creature holds the key to one of biology's most profound mysteries. The axolotl, a neotenic salamander, can regenerate entire limbs, spinal cords, and even portions of its heart with flawless precision. For decades, scientists have scrutinized this amphibian's miraculous abilities, but only recently have they begun mapping the precise activation patterns of stem cells at amputation sites—a discovery that could rewrite regenerative medicine.

The Dance of Stem Cells

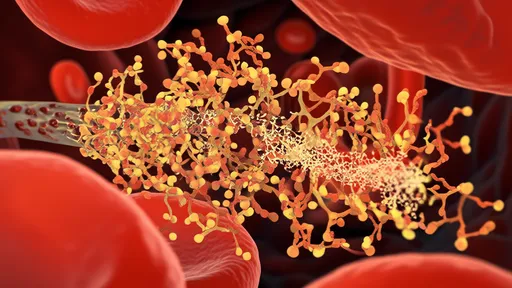

When an axolotl loses a limb, the wound site doesn't simply scar over as it would in mammals. Within hours, epidermal cells migrate to cover the exposed tissue while beneath the surface, a symphony of cellular reprogramming begins. Specialized cells called blastemal progenitors—often dubbed the "stem cell orchestra conductors"—start congregating at the injury site. These aren't ordinary stem cells; they retain a memory of their positional identity, remembering whether they came from a pinky toe or an elbow.

Advanced single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed something extraordinary: these cells don't activate all at once. Instead, they follow a precise temporal sequence, like dominoes falling in perfect rhythm. First, genes associated with wound healing switch on (TGF-β and FGF pathways dominate this phase). Then, within 48 hours, a second wave of genetic activity emerges—this time involving ancient developmental genes like Hoxa13 and Shh that haven't been active since the axolotl was an embryo.

The Cartography of Renewal

Researchers at the MDI Biological Laboratory recently published a spatial atlas of regeneration in Science Advances. Using fluorescent markers to track over 30 cell types, they discovered that regeneration isn't a free-for-all—it's a highly organized territorial reclaiming. Muscle cells only rebuild muscle; cartilage precursors strictly stick to joint reconstruction. This precision contradicts earlier theories suggesting complete cellular reprogramming into pluripotent states.

Even more astonishing is the role of nerve cells. Unlike mammals, where nerves merely transmit signals, axolotl neurons physically guide regeneration. When scientists experimentally prevented nerve fibers from reaching amputation sites, blastema formation failed entirely. The nerves appear to secrete a cocktail of proteins (including nAG, a nerve-derived growth factor) that serve as molecular batons, directing the stem cell orchestra.

Epigenetic Time Travel

The most groundbreaking revelation comes from chromatin studies. When a limb is lost, cells near the injury site undergo massive epigenetic rewinding—their DNA methylation patterns revert to an embryonic configuration. This "molecular amnesia" erases their specialized identity, granting temporary access to long-silenced developmental programs. But here's the paradox: while the cells regain plasticity, they never fully forget their original position. A wrist cell won't accidentally regenerate as a shoulder.

This phenomenon, termed "positional memory," relies on mysterious epigenetic bookmarks that survive the reprogramming process. Teams at the Whitehead Institute are now hunting these molecular placeholders—likely a combination of histone modifications and non-coding RNAs that persist like invisible ink on rewritten genetic instructions.

Cross-Species Implications

Mammals, including humans, possess most of these regeneration-related genes. The difference lies in their regulation. Our TGF-β pathways prioritize scarring over regeneration; our Hox genes remain locked in adulthood. Yet glimmers of potential exist: human children can regenerate fingertips before age six, and deer annually regrow antlers through blastema-like mechanisms.

Several labs are now testing "axolotl-inspired" cocktails to awaken dormant regenerative programs in mice. Early results show promise—partial digit regrowth has been achieved by combining nerve stimulation with epigenetic modulators. The real challenge lies in scaling this up for complex structures while avoiding uncontrolled cell proliferation (i.e., cancer).

Ethical Frontiers

As research progresses, difficult questions emerge. Should we enhance human regenerative capacities if it means tampering with evolutionary safeguards against cancer? How might lifespan extension through organ regeneration impact societal structures? The axolotl, oblivious to such dilemmas, continues regenerating as it has for millions of years—a living testament to nature's ingenuity.

What began as curiosity about a quirky amphibian has blossomed into one of the most transformative frontiers in biomedicine. The axolotl's regeneration playbook, written in the language of stem cells and epigenetics, may soon help us reclaim what was thought permanently lost—not just limbs, but perhaps hope for degenerative diseases once deemed incurable.

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025

By /Jun 9, 2025